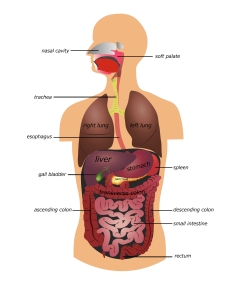

Medically, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is known by a variety of other terms: spastic colon, spastic colitis, mucous colitis and nervous or functional bowel. It is most often a disorder of the large intestine (colon), although the small intestine and even the stomach can be affected.

The colon, the last five feet of the intestine, serves two functions in the body. First, it dehydrates and stores the stool so that, normally, a well-formed soft stool occurs. Second, it quietly propels the stool from the right side over to the rectum, storing it there until it can be evacuated. This movement occurs by rhythmic contractions of the colon.

When IBS occurs, the colon does not contract normally. Instead, it seems to contract in a disorganized, at times violent, manner. The contractions may be terribly exaggerated and sustained, lasting for prolonged periods of time. One area of the colon may contract with no regard to another. At other times, there may be little bowel activity at all. These abnormal contractions result in changing bowel patterns, bloating, and discomfort.

A second major feature of IBS is abdominal discomfort or pain. This may move around the abdomen rather than remain localized in one area.

These disorganized, exaggerated and painful contractions lead to certain problems. The pattern of bowel movements is often altered. Diarrhea may occur, especially after meals, as the entire colon contracts and moves liquid stool quickly into the rectum. Alternatively or consecutively, localized areas of the colon may remain contracted for a prolonged time. When this occurs, which often happens in the section of colon just above the rectum, the stool may be retained for a prolonged period and be squeezed into small pellets. Excessive water is removed from the stool and it becomes hard.

Also, air may accumulate behind these localized contractions, causing the bowel to swell. So bloating and abdominal distress may occur. Some patients see gobs of mucous in the stool and become concerned. Mucous is a normal secretion of the bowel, although most of the time it cannot be seen. IBS patients sometimes produce large amounts of mucous, but this is not a serious problem. The cause of most IBS symptoms — diarrhea, constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain — are due to this abnormal physiology.

IBS is not a disease

Although the symptoms of IBS may be severe, the disorder itself is not a serious one. There is no actual disease present in the colon. In fact, an operation performed on the abdomen would reveal a perfectly normal appearing bowel.

Rather, it is a problem of abnormal function. The condition usually begins in young people, usually below 40 and often in the teens. The symptoms may wax and wane, being particularly severe at times and absent at others. Over the years, the symptoms tend to become less intense.

IBS is extremely common and is present in perhaps half the patients that see a specialist in gastroenterology. It tends to run in families. The disorder does not lead to cancer. Prolonged contractions of the colon and constipation, however, may lead to diverticulosis, a disorder in which balloon-like pockets push out from the bowel wall because of excessive, prolonged contractions.

Causes

While our knowledge is still incomplete about the function and malfunction of the large bowel, some facts are well-known. Certain foods, such as coffee, alcohol, spices, raw fruits, vegetables, and even milk, can cause the colon to malfunction. In these instances, avoidance of these substances is the simplest treatment.

Infections, illnesses and even changes in the weather or our circadian rhythms somehow can be associated with a flare-up in symptoms. The premenstrual cycle in females can also cause changes in the intestinal tract. By far, the most common factor associated with the symptoms of IBS are the interactions between the brain and the gut. The bowel has a rich supply of nerves that are in communication with the brain. Virtually everyone has had, at one time or another, some alteration in bowel function when under intense stress, such as before an important athletic event, school examination, or a family conflict.

People with IBS seem to have an overly sensitive bowel, and perhaps a super abundance of nerve impulses flowing to and from the gut, so that the ordinary stresses and strains of living somehow result in colon malfunction.

These exaggerated contractions can be demonstrated experimentally by placing pressure- sensing devices in the colon. Even at rest, with no obvious stress, the pressures tend to be higher than normal. With the routine interactions of daily living, these pressures tend to rise dramatically. When an emotionally charged situation is discussed, they can reach extreme levels not attained in people without IBS. These symptoms are due to real physiologic changes in the gut — a gut that tends to be inherently overly sensitive, and one that overreacts to the stresses and strains of ordinary living.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of IBS often can be suspected just by a review of the patient’s medical history. In the end it is a diagnosis of exclusion; that is, other conditions of the bowel need to be ruled out before a firm diagnosis of IBS can be made.

A number of diseases of the gut, such as inflammation, cancer, and infection, can mimic some or all of the IBS symptoms. Certain medical tests are helpful in making this diagnosis, including blood, urine and stool exams, x-rays of the intestinal tract and a lighted tube exam of the lower intestine. This exam is called endoscopy, sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

Additional tests often are required depending on the specific circumstances in each case. If the proper medical history is obtained and if other diseases are ruled out, a firm diagnosis of IBS then can usually be made.

Treatment

The treatment of IBS is directed to both the gut and the psyche. The diet requires review, with those foods that aggravate symptoms being avoided.

Current medical thinking about diet has changed a great deal in recent years. There is good evidence to suggest that, where tolerated, a high roughage and bran diet is helpful. This diet can result in larger, softer stools which seem to reduce the pressures generated in the colon.

Large amounts of beneficial fiber can be obtained by taking over-the-counter bulking agents such as psyllium mucilloid (Metamucil, Konsyl) or methylcellulose (Citrucel). You can also mix up your own fiber supplement.

As many people have already discovered, the simple act of eating may, at times, activate the colon. This action is a normal reflex, although in IBS patients it tends to be exaggerated. It is sometimes helpful to eat smaller, more frequent meals to block this reflex.

Diet changes are often effective and a good starting point. In addition to avoiding known food triggers, a special diet called FODMAP can also be used. This diet reduces the foods that are fermented in the colon and in turn reduce the painful bloating that can occur.

There are certain medications that help the colon by relaxing the muscles in the wall of the colon, thereby reducing the bowel pressure. These drugs are called antispasmodics. Since stress and anxiety may play a role in these symptoms, it can at times be helpful to use a mild sedative or antidepressant, sometimes in combination with an antispasmodic. No one drug is consistently effective in all people with IBS and treatment is often tailored to the patient and their symptoms. Antidepressant class of medications such as Serotonin blockers or tricyclic antidepressants are particularly helpful for tough cases.

Physical exercise, too, is helpful. During exercise, the bowel typically quiets down. If exercise is used regularly and if physical fitness or conditioning develops, the bowel may tend to relax even during non-exercise periods. The invigorating effects of conditioning, of course, extend far beyond the intestine and can be recommended for general health maintenance.

As important as anything else in controlling IBS is learning stress reduction, or at least how to control the body’s response to stress. It certainly is well-known that the brain can exert controlling effects over many organs in the body, including the intestine.

Summary

Patients with IBS can be assured that nothing serious is wrong with the bowel. Prevention and treatment may involve a simple change in certain daily habits, reduction of stressful situations, eating better and exercising regularly.

Perhaps the most important aspect of treatment is reassurance. For most patients, just knowing that there is nothing seriously wrong is the best treatment of all, especially if they can learn to deal with their symptoms on their own.